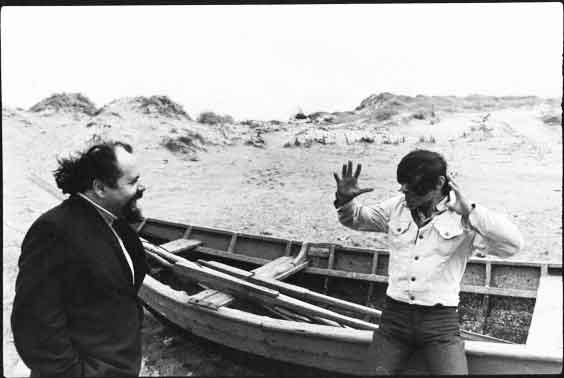

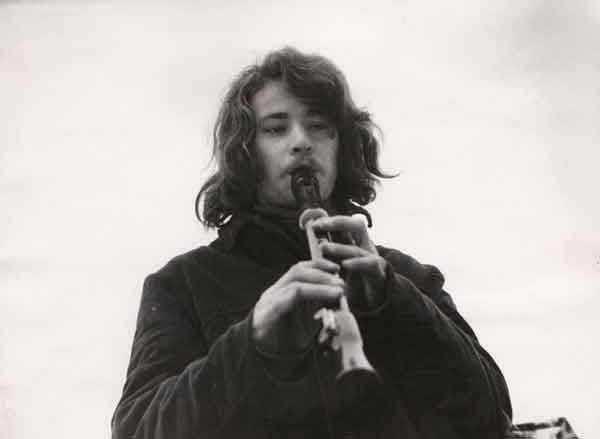

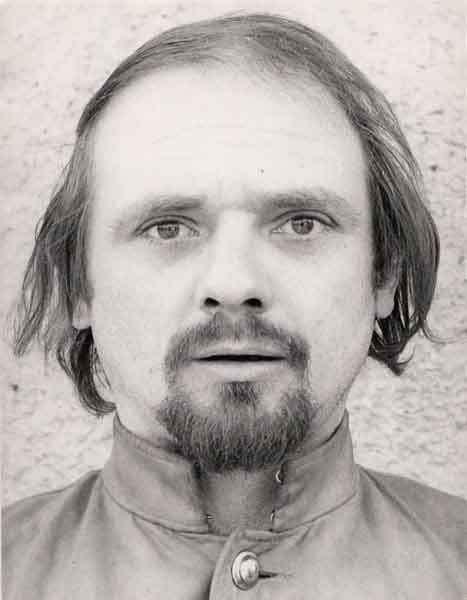

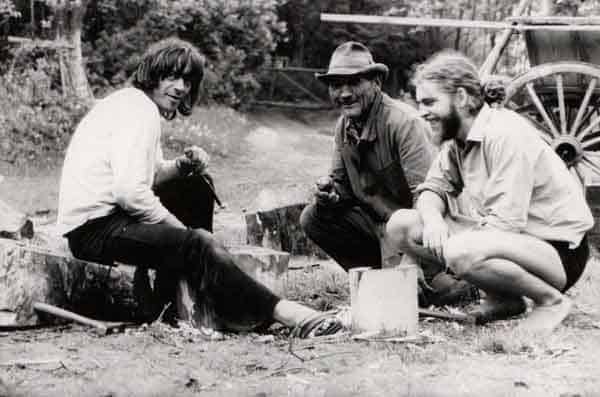

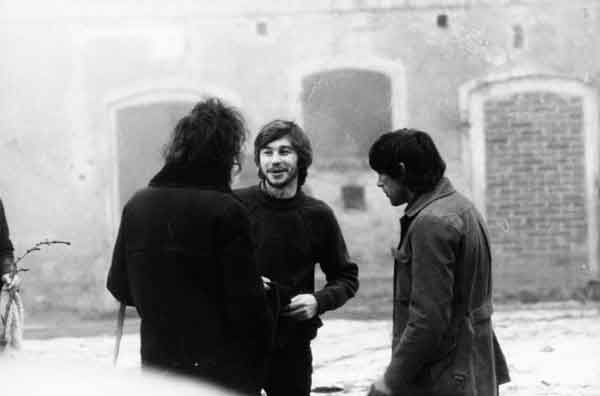

Exoduction was published for the first time in 1997, in the book The Grotowski Sourcebook , edited by Richard Schechner and Lisa Wolford (Routledge, New York). With some variation, the English text was then republished in 2001 and transferred to a digital edition in 2006. What we publish here is the "final" version of the text, provided by the scholar and not modified for publication in Italian in Sciami/Ricerche n. 4. The images that accompany the text are present in the archive of The Grotowski Institute and have been granted by the author, the photographer Andrzej Paluchiewicz. We thank the Polish Institute of Rome and in particular Anja Jagiello.

This essay by Richard Schechner dedicated to a mythical figure of the theater of the late twentieth century; a work of critical reconstruction that has contributed decisively to consolidating the legacy of Grotowski, just a few months after his death. In addition to fixing some essential terms of the vocabulary, together with the contents and the periodization of the Grotowskian work (aspects that Grotowski in life were entrusted exclusively to oral transmission), the essay retraces the formation of Grotowski, the aspects linked to his character, the specific forms of his research and his transmission of knowledge, the exercise of leadership, the role of his collaborators, the sources, the mystical side, his relationship with the spirit of time, the importance (and weakness) of his opera, in the history of twentieth century theater.

1.

He was a fox, eagle, snake, mole. A shape‑shifter, elusive, extremely powerful in the way he held people close or kept them distant, in either case dazzling them with his aura. His presence was scary to some, mysterious to others. His public appearances were largely just that, and were such for a quarter of a century or more before his death in January 1999. Grotowski appeared as an apparition, well‑controlled, with carefully calibrated doses of wisdom and evasion, insights and repetition.

Like the songs, dances, and rituals he and his colleagues harvested from many cultures, Grotowski mixed humility and arrogance, certainty and skepticism, simplicity and pomp. In Catholic Poland he said he was an atheist, but no one who knows his work believes that. But exactly what his religious beliefs were is not easy to say. Those who knew him best, have worked with him the longest, have shared whole days and weeks, say he could be witty, warm, friendly, and downright snugly.

2.

This attempt to locate Grotowski was written in 1997, two years before he died and slightly revised in 2000. It is the result of many years of contact with Grotowski, influence coming from him, and thinking about him and his work. Grotowski died on 14 January 1999 at the age of 65. To some he stands with Stanislavsky, Meyerhold, and Brecht as one of the great figures of twentieth century theatre. To others he remains virtually unknown. A strange paradox: this figure whose influence is not mostly through public productions but by means of the hundreds, perhaps thousands, of individuals he encountered, touched, and changed.

After a spectacular, brief career making plays for the public, around 1970 Grotowski decided to work either one‑on‑one or with very small groups. And even while making productions for the public, that public was small, usually no more than from 40 to 80 spectators. In such intimate settings, a performances was more an encounter than a distanced viewing.

As one who felt the heat of Grotowski’s gaze, and who will miss his presence most dearly, I need to write of his work, what makes it whole and unified, and its importance and impact. He was my teacher, and most especially so at the moment I was forming The Performance Group in 1967.

For many who met Grotowski encountering him was special, a Zen master’s slap on the face. I always approached him carefully, with Biblical fear born of respect. Not that he wasn’t also playful and ironic, generous and sympathetic. He could go from support to icy sarcasm in a flash. It was hard to look deeply into his eyes, the conventional “mirror of the soul,” because either you gazed at eyes reduced in appearance by thick glasses or when he took them off, a squint. His health was frail yet he didn’t take care of himself. He smoked, he ate erratically. Once, in a California restaurant, he ordered a very large steak, asked it to be singed only, and tore into the raw meat. “I am a wolf!” he exulted.

Of what matter are these personal details? I know that others will have very different descriptions and experiences. We are all blind men giving opinions about the elephant. Grotowski shaped himself to suit his encounters with individuals. In his work one on one he had an unparalleled gift to enter into what Martin Buber called the “Ich du,” the I you, relationship. His shape shifting was not trickery or avoidance, but meant to better drill to the core of the matter. His appearance was liable suddenly to change radically, as when in the late 1960s he morphed from being a chubby smooth faced man in a dark suit and sunglasses to a skinny long haired type in a blue jean jacket toting a backpack a cross between a hippy and a martial arts master. He slept God knows when, certainly not at night when he exulted in his work.

Grotowski became known outside his native Poland through his writings, interviews, and a series of tours in the 1960s and 70s of his Laboratory Theatre to Western Europe, the Middle East, Mexico, the U.S.A. and Australia. This was during and just after his “theatre of productions” phase (1957-69). The group performed in New York in 1969 and in Philadelphia in 1973. Performances of “The Constant Prince,” “Akropolis,” and “Apocalypsis cum Figuris” deeply stirred the American theatre across the board.

What was it like to attend one of Grotowski’s theatre pieces? Writing for the New York Times on November 30, 1969, Walter Kerr–no friend of experimental theatre–described his own experience with the Polish Laboratory Theatre:

It occurred during ‘Akropolis, the piece in which Jewish and Greek legend run together like a blood puddle at Auschwitz. The center of the stage, a construction of gas pipes, bathtubs, and wheelbarrows gone rusty, was for the moment emptied of actors. We, sitting directly on the stage, were closer to the core of things than the performers were. We were aware of one another and in occupation. The performers were all behind us, scattered in the unidentified dark, making rushed, whispering sounds that felt as though the walls of a room were hurrying to meet a corner.

A sudden sibilant raked my ear; the speaker was near my shoulder. I didn’t turn to see who it might be. A body was thrust violently past and above me, to land with a thud in the wheelbarrow an inch from my head; I didn’t shy, or think I was going to be struck. I looked at the audience’s faces, opposite and to the left. Almost all were open‑mouthed as the actors emerged into light again, wooden soles stomping, eyes heavy‑lidded and vacant white, shoulders thrust forward to jab at other bodies in erratic rhythm; otherwise, those faces were entirely composed.

But despite his excellence as a theatre director, Grotowski’s deeper interests lay elsewhere.

In 1956, while still a student, he undertook a two‑month trip to Central Asia. Later he journeyed often to many parts of the world in search of masters of ritual performances. Grotowski invited some of these to work with him in California or Italy. He investigated techniques of Balinese, Haitian, and Hindu rituals, Chinese martial arts, the Egyptian “Book of the Dead,” Shaker songs, and more. He engaged in conversations with anthropologist Barbara Myerhoff and scholar‑turned‑guru Carlos Castaneda. He searched not only widely, but back in time seeking to recuperate ancient rituals whose traces were hardly visible.

By the 1970s, ordinary theatre, even the most radical experimental theatre as was performed by the Laboratory Theatre, no longer satisfied Grotowski. Protean as always, Grotowski disbanded his company (it was formally dissolved in 1984), and began working in “paratheatre” (1969‑78), an effort of stretching the relationship between performers and spectators. Paratheatre led to “theatre of sources” (1976‑82)‑‑an attempt to find in older traditions, both Western and non‑Western, the core or essence of theatre. Grotowski described the theatre of sources as “the meeting between the old one and the young one,” in both the personal and cultural senses.

Paratheatre involved at times thousands of people, ranging far and wide both conceptually and actually. This melee proved unsatisfactory to the highly disciplined Grotowski, who moved on to “objective drama” (1983‑86) which was focused on a limited number of participants in a special program designed by and for Grotowski at the University of California, Irvine. In objective drama Grotowski wanted to combine “source materials” with the precise kinds of training and individual exploration of the actor’s instrument he had developed during his first years as a director. This kind of focused investigation continued in Grotowski’s ultimate phase, “art as vehicle” (1986‑until his death, and beyond).

During this last phase, as his health failed (he had heart trouble, kidney disease, and leukemia), he picked as his successor Thomas Richards, the son of American director and educator Lloyd Richards. Grotowski conveyed to Richards all that he could.

Grotowski’s influence is everywhere in theatre. Sometimes the mark is direct, as with Eugenio Barba’s Odin Teatret in Denmark, Vladimir Staniewski’s Gardzienice in Poland, or James Sloviak’s and Jairo Cuesta’s New World Performance Laboratory of Cleveland, Ohio, U.S.A. Sometimes the influence is not easily discernible on the surface, as with The Performance Group and through it to the Wooster Group, or Joseph Chaikin, Peter Brook, and Andre Gregory, to name just a few of many.

Grotowski’s effects on the theatre flow from three ideas that he identified, explored, and attempted to systematize. First, that powerful acting occurs at a meeting place between the personal and the archetypal–in this he continued and deepened the work of Stanislavsky. Second, that the most effective theatre is the “poor theatre”–one with a minimum of accoutrements beyond the presence of the actors. Third, that theatre is intercultural, differentiating and relating performance “truths” in many cultures.

He explored these ideas over decades of precise, detailed, systematic, physical, and spiritual work. It was in his actual working with people, his scrupulous and incisive attention to detail, his uncanny insights into the performer’s process, that he made himself most clear. His writings can appear inspirational or opaque. But actually working with him was another matter altogether. He belongs to oral tradition.

3.

The last time I saw Grotowski was in Copenhagen in 1996. We sat in the corner of crowded room drinking coffee. Though nearly his age, I felt like his son. When I learned of his death, I wept.

There were happier times. I remember his 49th birthday, 11 August in 1982, at Andre and Chiquita Gregory’s Central Park West apartment. There were people there, but not a big crowd. 11 August is also Carol Martin’s birthday, so we were celebrating together, drinking, eating. The Grot put away a lot of vodka and champagne, me less, Carol champagne only. Suddenly, Grotowski began singing, “Fucky birthday to you, fucky birthday to you, fucky birthday, fucky birthday, fucky birthday to you!” Then he seized a champagne bottle, gave it a shake, anbd began squirting the bubbly all over us. I responded in kind. Soon many at the party began splashing each other, singing, and laughing.

I suppose it is nothing unusual for a person to have many aspects, many faces, many presences, many characters (as in the theatre). This multiplicity of roles is something Grotowski finds in Gurdjieff, a researcher of the mindbody spirit with many affinities to Grotowski. “We are all continuously playing a character, a role; it is what Jung defined as persona” (Grotowski 1996:100). And in that nearly undecipherable concept, presence, Grotowski’s mastery is most manifest. More than any of his actors, including the great, tragic Ryszard Cieslak, Grotowski was and continues to be a presence. Exactly what that means, how it works, and what consequences it has for theatre and beyond is the subject of this writing.

4.

The basic bio‑data of Grotowski’s early life, until he entered theatre school in 1951, are well‑known, but skimpy (see Osinski 1986: 13‑14 and Kumiega 1985:4). As Kumiega summarizes it:

Grotowski was born in Rzeszow, near the Eastern border of Poland, on 11 August 1933. His father worked in forestry and his mother was a schoolteacher. His only brother [Kazimierz], three year his senior, was to become a professor of theoretical physics […]. At the outbreak of the Second World War, at the age of six, Grotowski settled with his mother and brother in the small village of Nienadowka, about twenty kilometres north of Rzeszow (his father having left Poland to settle in Paraguay, where he lived until his death in 1968). The small Grotowski family spent the entire occupation in these rural surroundings. […]. In 1950 the family moved again, to Cracow, where Grotowski completed his secondary education (although he had earlier missed a year due to a serious illness). In July 1951 he applied for admission to the Acting Department of the State Theatre School in Cracow […]

No other work in English gives us more1.

The Grotowski the world knows begins in Opole with the establishment in 1959 of the Theatre of 13 Rows. Begins, in fact, when Grotowski can ration what is known. Osinski gives some account of Grotowski’s earlier theatre work, his activism during student days, his lectures on “oriental philosophy,” and his 1956 trip to “Central Asia” (Osinski 1986: 18). But these accounts are bloodless facts, not a life2.

What about boy Grotowski’s experiences just before and during World War Two? What were the formative incidents of his childhood? I discussed this period of his life with Grotowski in 1996. I did not tape record that meeting, so what follows are paraphrases of what he told me. In the years before World War Two, the economic situation of the Grotowski family “descended to the level of the Polish peasant.” During the war, Grotowski and his mother lived in a very small village near a forest. His father went to Paris to join the Polish exile army. Jerzy would never see him again. After the war, his father emigrated to Argentina and then to Paraguay where he died in 1968, working first on the docks and then later for the British consulate. He said he would not live in a Poland dominated by the USSR. “He was a sculptor and a forest ranger,” Grotowski told me. But it is Grotowski’s mother who formed the young artist’s mind and work. He always speaks of her with deep love and respect. I am paraphrasing (I did not tape record our conversation):

Mother was a very wise woman. She worked as a school teacher when she could. But she also worked cleaning houses, doing manual labor‑‑whatever it took to provide for her small family [Jerzy and Kazimierz]. She always kept books of different religions on the shelf [where young Jerzy would have easy access to them]. Christian, Jewish, Hindu, Buddhist. She would say that these were all different but also really all the same, they are all speaking about the same essential truths. […]

Once during the war the Germans gave people soap. But my mother said not to use it, that the soap was made from Jewish bodies. But we had actually very little information about what was going on. There was talk, we heard talk.

More than talk. Grotowski told me he saw corpses in the forest. The Germans entered houses in the village, he heard shots. He was a boy of 6 when the war began, 12 when it ended. Akropolis, ostensibly about Auschwitz, is also about what Grotowski felt, saw, and reacted to during the war, including reading classic texts in the midst of a world that ignored or brutally parodied what these books said and meant.

The genocidal Nazi occupation segued into the complicated oppression‑permission‑oppression dance of the Communist years, climaxing in the Solidarity movement, martial law, and finally the collapse of Communism. After the imposition of martial law in December, 1981, Grotowski avoided Poland for nearly a decade. He returned in April 1991 to accept an honorary doctorate from Wroclaw University and to share his recent work with young people and old friends by screening of Mercedes Gregory’s film of Downstairs Action3.

In December 1996 and February-March 1997, Grotowski traveled to Warsaw and Wroclaw to discuss his Art as Vehicle work and to receive two awards, the Konrad Swinarski Prize and the Grand Prize of the Polish Culture Foundation. But despite these trips, since Theatre of Sources, Grotowski has mostly worked outside of Poland. Some have wondered why Grotowski did not get himself involved directly and deeply in Solidarity. In fact, the young Grotowski was politically active during the “Polish October” of the mid-1950s. But by the time he joined the Theatre of the 13 Rows in Opole in 1959, this direct involvement in politics subsided. In truth, Grotowski is no more a political person in the Solidarity sense than he is a theatre person in the Broadway sense. He eschews actions that bind him to groups beyond his own circle; when he interacts outside that circle, it is entirely on his own terms, dictating how questions are to be put to him, the hours of meeting, the people he will meet with. To his Workcenter in Pontedera stream those wanting to learn more about what he is doing. At the Workcenter they participate in carefully regulated encounters.

We are not likely to find out what the young Grotowski was thinking from 1945 into the mid‑1950s. His tracks before the emergence as a brilliant young auteur‑director are covered or destroyed by the war, its aftermath, the Russian occupation, and the Cold War. The man himself is not eager to open his life history. Like G. I. Gurdjieff‑‑a figure resembling Grotowski in key ways, and about whom I will write later‑‑Grotowski journeys into Central Asia, India, and China where he meets “remarkable people,” acquires esoteric knowledge, practices yoga, develops his opinions about human life. Several times later in life, Grotowski leaves his colleagues, steps out of sight, journeys into Asia or across America. When he re‑emerges in New York, Warsaw, or Wroclaw he is changed, but the process that led to the changes are not spelled out. His is a life constructed, an auto‑biography written with doings and results rather than words and explorations.

Grotowski plays his cards very close to his vest. Nor do I feel right in getting too personal about him. Did he have a sex life? If so, who were his lovers? Was his “orientation” (what a weird gyroscopical word) “straight,” “gay,” “bisexual,” or something else? Does it matter in relation to his work? Was it appropriate for me to reveal his fucky birthday caper? To what degree ought what is private about a well-known person be left alone? Why am I worried? Why should Grotowski so thoroughly control what gets out about him? Is this control central to his work? The control steers all inquiries about the man to his work, giving the impression, which amazingly may be the truth, that the work is all there is of the man. Like a noh master, Grotowski lives a strictly bounded life, measuring carefully even his journeys, his times out. But if his private life and innermost creative processes remain more or less secret, “the Grotowski work,” if I may be permitted to term it as such, has been very widely disseminated. This is all the more amazing because Grotowski is not the author and director of his own plays (as Brecht was), nor an author, actor, director, and teacher of actors (as Stanislavsky was), nor even the director of enormously popular productions, as Brook is.

5.

The Grotowski work is fundamentally spiritual. People say Grotowski “left theatre,” but the fact is he was never “in theatre.” Even in his early stage productions, theatre was his path not his destination. Ready to enter university, Grotowski had three possibilities: theatre training, Indian‑Hindu studies, medical school (“not to heal the sick,” he told me, “but to become a psychiatrist who would help healthy persons develop their insights into life”). He chose theatre because he concluded that there he would encounter the least censorship and mind control. Censors read words, the scripts submitted to them. They were not concerned with staging. Censors cared about what was put before the public, what could be quoted and circulated, not what happened during workshops or rehearsals. So it was the non-verbal aspects of theatre that Grotowski developed most intensely. It was the pre‑public or non‑public part of theatre, the long process of preparation, where Grotowski took the greatest risks, exposed himself and his co‑workers to each other. And he gathered around him in the Laboratory Theatre individuals like himself.

To the outer world [Grotowski told me in 1996] the Lab presented an image of unity and solidity. But the people themselves were very “risky” and often marginal, highly charged, risk‑taking. The Lab was an incredibly anarchic group. The work often verged on chaos. Intense. Much passion and fighting within. This was natural because that kind of work, at that time, in that Polish society, would of course attract people who were risk‑takers, wo would go to the edge, to the extreme.

The Lab’s public performances played to minuscule audiences. The pieces were gestural and musical, uttered and sung rather than spoken, personal to the point of intimacy, but not easily decipherable, not for a large public. Word texts drawn from classics were broken into fragments, remolded into a montage of soundscapes and complex vocalizations, hard to follow, unlikely to draw either large crowds or the censor’s fire.

But underneath these public shows, Grotowski and his “colleagues” (a term he favored, a kind of non-Communist “comrades”) used theatre to pursue spiritual, mystical, and yogic interests. Grotowski himself would not use the word “spiritual,” he would more probably mock the idea. But I don’t know what other word encompasses his quest, his methods, his journeys, and his vocabulary in interviews and writings. His is not an obscurantist mysticism, but one connected to the ancient tradition of gnosis and the Hasidic figure of the exiled, wandering Shekhinah: a search for “scattered truth,” sparks hidden in far‑away places, barely discernible, in need of gathering, re‑assembling, re‑connecting. Grotowski’s goal was, and is, to approach‑‑ yet not grasp, hold, possess, or in any way squeeze to death‑‑a definite and particular kind of spiritual knowledge. This knowledge, though concrete and expressible in terms of sound and movement, is ineffable, not translatable into words. That is why it so often takes the shape of song, “action” or “motions.” The more ordinarily theatrical aspects of the Grotowski work have been codified by Eugenio Barba, the earliest and most loyal dissemenator of the work, and probably Grotowski’s most theoretically inclined disciple. In 1991, Barba (with Nicola Savarese), published A Dictionary of Theatre Anthropology a book whose theorems are not Grotowski’s as such but are closely related, fruits of the same tree. What Grotowski will permit to be written down about his recent way of working, the Art as Vehicle phase, is in Richards’ At Work with Grotowski on Physical Actions (1995). Many entries in the Grotowski Sourcebook (1997) tell what it was like to participate or witness this or that Grotowski project. But for all this telling, little is known of the interior processes of Grotowski’s mind. Nor will he leave behind a set of textbooks and a biography, as Stanislavsky did; or reproducible theatre works, as Brecht did. Grotowski’s processes are much more coherent than Artaud’s, and he has trained, or at least deeply touched, many persons. But his legacy is to some degree equivalent to Artaud’s: elusive but strong, open to many interpretations, a “story” maybe even more than a “system.” Like a rock thrown into a lake, Grotowski will disappear. He will be known only through the ripples.

6.

Grotowski transmits what he knows by means of an oral tradition. His deepest ways of working cannot be reduced to written discourse. His “way” is the actual work process itself. This process is not shared with many people simultaneously. At any given time, Grotowski works with less than a dozen persons, and those he really shares with may be only one or two. Visitors come and go to Pontedera, but not in large numbers. Earlier, the Laboratory Theatre was a small enterprise in terms of numbers, its working methods sealed off from the public; and even the spectators numbered less than 100 for any given performance. Only in the 1970s during the paratheatrical phase, did Grotowski open his work to a large number of people. And even then, what he judged the “real” work of the paratheatrical period was conducted by a small, closed group, those Grotowski considered the “guides” of the rest.

Grotowski thinks in action, or in active reflection, a one‑to‑one intense process. This method has not changed much through the various periods of his work, from the “Theatre of Productions” through “Paratheatre” and “Theatre of Sources,” and on to “Objective Drama” and “Art as Vehicle.” What unites all these periods, despite their diverse objectives, different styles, and fluctuations in the number of people participating, is Grotowski’s insistence that what he has to offer can be acquired only through direct contact, person‑to‑person interaction, Martin Buber’s “ich und du”: the oral tradition.

Grotowski has written no book. Most of what is published under his name are records of meetings or interviews. Of the fourteen items in Towards a Poor Theatre, only four were written by Grotowski. I am certain that if the sources of these four were looked into further, they would also be found to originate in talks or workshops. Of the five great forces in European theatre in the twentieth century‑‑Stanislavsky, Meyerhold, Brecht, Artaud, and Grotowski‑‑Grotowski is the least writerly. He distrusts words as such, privileging inwardly focused bodymind work, psychophysical work, direct personal contact that operates on the psyche (which in its original Greek meant “soul”) “like a scalpel,” as he on more than one occasion has remarked, cutting through the ephemeral and getting at‑‑revealing and releasing‑‑ the essential. Here again the notion of “spiritual” enters in its etymological sense as “breath”: utterance, voice, song. Of course, the assumption that there is an essential needs to be examined critically. But for the moment, take Grotowski at face value.

Many teachers, from Buddha and Socrates to Jesus and the Sufi masters, lived the oral tradition, even if subsequently their teachings were written down4. In Meetings with Remarkable Men (1963: 36), Gurdjieff tells how his “whole future destiny” depended on his recognition of how the oral tradition can bring forward in time materials from very very far back. He writes how in the ruins of what had been ancient Babylon were found tablets with the story of Gilgamesh engraved on them.

When I realized that here was that same legend which I had so often heard as a child from my father, and particularly when I read in this text the twenty‑first song of the legend in almost the same form of exposition as in the songs and tales of my father, I experienced such an inner excitement that it was as if my whole future destiny depended on all this. And I was struck by the fact, at first inexplicable to me, that this legend had been handed down by ashokhs [Asian and Balkans, local bards] from generation to generation for thousands of years, and yet had reached our day almost unchanged. (1963:36)

Gurdjieff depended on “orature”5 rather than literature to disseminate his work. He instructed that his own core text, Beelzebub’s Tales to his Grandson, be read aloud to students.

Grotowski believes various existing oral traditions link back to ancient practices. He both sent colleagues out to search for, brought “masters” in who could perform, elements of these traditions. This was the work especially during Theatre of Sources and Objective Drama. What was sought were archetypal or “essential patterns’ of movement, gesture, utterance, and song. Not only were these essential patterns learned by his core group, they were used as tools to activate inner intimate processes. The meeting of the essential patterns and the inner processes led to Downstairs Action and Action, the two performances thus far emanating from the Art as Vehicle phase of the Grotowski work6. Searching for the essential relates to Grotowski’s travels to Central Asia, China, and India. The conviction that the essential patterns brought forward in time by oral traditions will converge with materials uncovered within individual performers by means of a rigorous inner process relates to the Hindu belief in the identification of Brahman (the ultimate universal Self) with atman (the individual Self). Each person, if properly trained, can experience the identicality of atman and Brahman. When trained, touched, found, liberated, experienced (which is the right word? no word is right), all boundaries between the individual and the ultimate evaporate. Different religions have different terms for this: moksha, enlightenment, ecstasy, rapture, nirvana‑‑words differ as the emphasis changes, from achieving the all to merging with the divine to reaching the end of the path that is no‑path.

At the intersection of the most intimate-personal with the most objective-archetypal, Grotowski’s doers construct actions which are presumed to be the distilled essence of what is abiding, ancient, and true, in human life. Warning against “self‑indulgence,” as he has done throughout his career, Grotowski caustically denies that people can find the essential without undergoing the most rigorous and committed training. The atman is not easily or casually accessed. What is essential can be researched only by means of a disciplined process joining what is learned from those who know to what is found inside the individual self. This self, as I have noted, is the Hindu atman‑Brahman impersonal Self, not the ego‑driven narcissistic self of daily life. What I am outlining here is Grotowski’s process as I understand it, and the assumptions upon which that process is founded. I must put aside for now the question of whether or not such deep patterns or archetypes exist.

Grotowski lives and works within the oral tradition. That’s one of the reasons why he’s hard to pin down. One finds Grotowski not in a collection of texts, a film vault, or anywhere other than in the people he engaged with, poured himself into. And these persons changed or died, even as they passed on “the work” as they received it and interpreted it. At each phase of his professional career, Grotowski deeply engaged only a few persons, often confiding mostly in one key figure designated at the time to receive the teachings. In the Theatre of Productions it was for a time Zbigniew Cynkutis, then it was Ryszard Cieslak. During Paratheatre it was Jacek Zmyslowski until his death in 1982. At present, for Art as Vehicle, it is Thomas Richards of whom Grotowski writes:

The nature of my work with Thomas Richards has the character of “transmission”; in the traditional sense‑‑in the course of an apprenticeship, through efforts and trials, the apprentice conquers the knowledge, practical and precise, from another person, his teacher. A period of real apprenticeship is long and I have worked with Thomas Richards for eight years now [1993] (Richards 1995:x).

This is the way of the oral tradition.

Among those working with Grotowski there was conflict concerning who was the chosen one. I remember speaking to Cynkutis in 1985, about two years before he crashed himself to death in an automobile accident that some say was suicidal. Cynkutis spoke excitedly about the Drugie Studio Wroclawskie (the Second Studio of Wroclaw‑‑Grotowski’s Laboratory Theatre being the “first studio”). Drugie Studio was located at Rynek‑Ratusz 27, the former home of the Laboratory Theatre. Cynkutis intended the work to carry on Grotowski’s theatre of productions tradition. Standing in the freezing cold on the small balcony of his Wroclaw flat, watching through a gray icy drizzle as the traffic scooted by below us, Cynkutis insisted that he was Grotowski’s chosen one, the rightful heir to the methods and aura of the Laboratory Theatre.

On 11 February 1986, Cynkutis hand‑wrote me a letter in English detailing just how he intended to continue Grotowski’s work:

After three months of rehearsals with the Polish and International group we have inaugurated a sequel of premieres of the project Phaedra‑Seneca. If I were to evaluate what has happened due to this opening I would have to stress the crossing of the barrier of psychological fear. For me and my colleagues, for many people of the Wroclaw artistic center the period of speculations and uncertainty finished. The speculations oscillated among respectful and emotional desires for mummification of a myth, turning the former building of Grotowski’s theater into a museum and a monument of his theatrical achievements.

There is a thing existing: in the same building, however with a totally changed function of the interior, the next generation of actors presents their work every evening. Again people under the age of 25 search for their own way of expressing those feelings which brings present reality, without destroying others’ achievements.

I serve them as old boat in which they can pass over all the litter of routines and habits which very easily cling to each new enterprise. I serve them with my knowledge, I discipline them to go further, not to rest where someone else has already used his energy. Hence I am neither a good and beloved daddy, nor a romantic leader pointing to a certain direction. I am a difficult witness and I stimulate them to an escape from that which is worthless [sic]. I convince them with the discipline of work, sincerity of demands, and knowledge of undertaking certain tasks by using already known tools. […]

I wish you could see what we have been doing. However, I expect the most interesting phase after two or three years of work when my activity will stimulate an initiative of a young director, and he himself, taking the theatrical basis and tradition will create in this place a new and important act. I believe in it‑‑that is why I decided to direct the Second Studio of Wroclaw. […]

The car wreck prevented Cynkutis from experiencing “the most interesting phase.” After his death in 1987, the Drugie Studio continued on and still existed in 1995 (according to an article in the Polish journal Notalnik Teatralny). But people tell me that the work is “wretched,” not a continuation of what Cynkutis wanted, no less Grotowski.

Many of Grotowski’s closest associates have had bad luck. Cieslak, Zymslowski, and Chiquita (Mercedes) Gregory were taken by cancer, Cynkutis in the car wreck. Antoni Jaholkowski and Stanislaw Scierski also died young. Of these I knew Cieslak and Gregory best. In the years before his death in 1990, I detected in Cieslak a broken heart caused by Grotowski’s decision to end the theatre of productions. I remember five minutes with Cieslak, in 1976, on a grassy slope outside Warsaw, in the midst of the only Grotowski paratheatrical event I ever took part in. Cieslak and I were alone. I addressed him with words to the effect that, “Grotowski is one of the great theatrical directors, and you one of the great actors. But now you are not acting anymore, you are not exploring roles like the Constant Prince or the Simpleton of Apocalypsis cum Figuris. You are running around in the countryside leading amateurs who crave God knows what kind of experiences. How do you feel about that?” Cieslak fixed me with his immense, heavy, powerfully sad brown eyes. “I have given myself to Grotowski, and I will follow him wherever he goes.” End of query, but not the end of the story.

Cieslak did not follow Grotowski, exactly. He taught many workshops, he acted, he tried directing. The last role I saw him play was as the blind king Dhritarashtra in Peter Brook’s The Mahabharata. Dhritarashtra’s open yet unseeing eyes belied the tragedy of Cieslak’s later life. This actor was equipped for Grotowski only. Not even Brook could replace the Polish master.

Once deprived of Grotowski‑as‑director, Cieslak smoked and drank himself to death. His final job, before lung cancer choked him, was as leader of the “Cieslak Studio” at the undergraduate drama department, Tisch School of the Arts, NYU. The announcement for that studio read:

Ryszard Cieslak, co‑founder with Jerzy Grotowski of the Polish Laboratory Theatre, will remain with us for another year to form a one‑year ensemble track/studio that will focus on the variety of training techniques that gave rise to the Grotowski/Cieslak as the Master Teacher [sic], but will also involve teachers of the Polish Mime Tradition, acrobatics, third‑world music and dance (African, Brazilian, Asian), vocal training, and magic technique. The ensemble will most likely develop and show a project or series of projects in late spring 1991.

“Master Teacher” was a joint being, a Grotowski‑in‑Cieslak, designating the closest relationship, that of “transmission,” from Grotowski to his disciple. This is why Cieslak was listed as a co‑founder of the Laboratory Theatre although he did not join until October 1961 at the start of the Lab’s third year. It was absolutely necessary for NYU and Cieslak to claim the originary moment, the singular foundation point.

Similarly, when the Lab disbanded in 1984, the statement published in Wroclaw’s Gazeta Robotnicza was signed by Cieslak and three other “founding members.” No lie was told in either case because by the 1980s the oral tradition had fused Cieslak with Grotowski. The myths of the oral tradition are stronger than the written record. According to that record, only Ludwik Flaszen, Rena Mirecka, and Zygmunt Molik were in the Laboratory Theatre from beginning to end, 1959‑1984. Grotowski himself was not among the signers. In their statement they wrote, “Each of us remembers that our origins lie in the common source whose name is Jerzy Grotowski, Grotowski’s theatre. […] . After 25 years, we still feel close to one another, just as it was in the beginning, regardless of where we are now ‑‑ but we have also changed.” What matter that Cieslak trod that path for 23 years, not 25? And why did Cieslak sign the statement and Grotowski not? Cieslak signed as himself and as a stand-in: over time no one was more closely identified with Grotowski than Cieslak.

Grotowski did not sign for two reasons. Pragmatically, having claimed political asylum in the United States, and not wishing to endanger his colleagues still in Poland, Grotowski was extremely careful regarding direct contact with them. He mainly communicated with them through Flaszen who was living in Paris, as he still does. But Grotowski did not sign also because his spirit inhabited the entire project, the unamed first cause, too necessary, powerful, and obvious to have his name written down with the others. As in his productions, he was all‑present by means of his absence, like God.

Control

Grotowski suffers from heart and other ailments that put him up against death. Conscious of his frailty, he studiously oversees his realm and his inheritance. Having no fortune in money or goods, he need write no complicated will. But how to measure and distribute his knowledge and authority is another matter. Is the Grotowski work heritable, and if so, who will inherit it? At the present phase of his life’s work, a period which appears to be ultimate, Grotowski is intensely concerned with how and to whom what he knows will be passed on. His relationship to Richards turns on this matter of transmission. Speaking of the oral tradition and Gurdjieff, a spiritual leader Grotowski says was only “somewhat important” to him, but in whose life and practices I find many compelling parallels, Grotowski reveals much about his own work:

It is a terrible business, because there is, on the one hand, the danger of freezing the thing, of putting it in a refrigerator in order to keep it impeccable, and, on the other hand, if one does not freeze it, there is the danger of dilution caused by facility. […] The burning question is: Who, today, is going to assure the continuity of the research? Very subtle, very delicate and very difficult (Grotowski 1996:101).

Here I recall Gurdjieff’s last words, spoken on 27 October 1949, to Jeanne de Salzmann‑‑the closest of his collaborators and his chosen heir:

The essential thing, the first thing, is to prepare a nucleus of people capable of responding to the demand which will arise…So long as there is no responsible nucleus, the action of the ideas will not go beyond a certain threshold. That will take time…a lot of time, even (Moore 1991:315).

Which leads me to a dark side of Grotowski, his need to control. This need is driven by his double sense of himself as immanently mortal and as the source of powerful, useful knowledge. Because there is much more about him than by him, Grotowski tries to control what materials are disseminated. This Sourcebook is a case in point. Before releasing texts and interviews with by him, Grotowski wanted to go over the table of contents of the book. He and Richards wanted to make certain that everything they wrote or said was exactly how they wanted it to be, even if upon occasion this went against standard grammar and word usage. On almost every item, Wolford, I, and Grotowski agreed. But on Philip Winterbottom Jr.’s “Two Years Before the Master” (1991), we did not. The article in TDR is a cutdown version (I did most of the editing) of a 100 page journal Winterbottom kept of his participation in the Objective Drama project in Irvine, from January 1984 to April 1985. In his journal, Winterbottom speaks not only about working with Grotowski, but about how he reacted emotionally to his teacher.

The more he uses me the more fulfilled I feel. I fear my own failure in this project; that fear is always with me. […] When Jerzy met me tonight, all my fears were put to sleep by his beautiful, childlike, brotherly smile. I gushed. […] (1991:142, 145, 146).

Most of what TDR published of Winterbottom’s journal was not this personal. Nor was Winterbottom critical of Grotowski, far from it: he writes as one yearning to have an emotional attachment to Grotowski, a hopeless yearning because Winterbottom clearly recognized that for Grotowski “the bottom line was always the work” (1991:154). Grotowski was vehement in his opposition to including selections from Winterbottom’s diary. Winterbottom’s account was inaccurate, we were told. Good enough, but other accounts of Grotowski’s work, especially of the paratheatrical events, some included in this Sourcebook, are subjective and “inaccurate.” And Winterbottom was hardly an outsider with just a casual experience of Objective Drama. He was a full participant in the work. I think Grotowski was queasy about Winterbottom’s adoration. The choice was stark: use the Winterbottom and lose Grotowski. If Wolford and I decided to publish “Two Years Before the Master” in this Sourcebook, we would get not one iota of cooperation from Grotowski or those in his inner circle. I did not cave in immediately. I asked the opinion of three persons who knew Grotowski’s work well. One did not reply. Another, who was not in Objective Drama, liked Winterbottom’s piece. The third person, a participant in Objective Drama, condemned the article as being inaccurate and sentimental. Wolford, who was in Objective Drama, also said that Winterbottom’s journal did not give an accurate description of the work. I agreed to drop the Winterbottom. But was I doing so in the interest of “accuracy” or because of Grotowski’s threat? Finally, I didn’t want to sacrifice the Sourcebook on the altar of my authority as editor. Anyone interested can get TDR and read the Winterbottom.

The Winterbottom incident is indicative of Grotowski’s lion‑like determination to keep a tight hand on what how his work is received and interpreted, what is published under his imprimatur, who gains access to his presence, the work at Pontedera, the film that Chiquita Gregory made of the Art as Vehicle work as it was in the 1980s. But to say that Grotowski controls his work is not to say that the work is closed. By 1966, more than 150 groups had seen the operation at Pontedera. But they witness what happens on Grotowski’s terms. There are no places available to the general public on a first come, first served basis. Has Grotowski absorbed the Polish and Soviet penchant for controlled history? Or the opposite, having experienced what can happen in a totalitarian state, will he always be fearful of the damage information can do, how fragile his reputation and situation? His need for control goes beyond responding to outside pressures or models. It is part of the traditions he follows: the hierarchical Roman Catholic church (Polish edition), the Indian guru‑shishya relationship, the hasidic rebbe, surrounded by adherents hanging on his every word, arguing and interpreting, guarding him from intrusions.

Sources Near and Far

Grotowski’s own oral tradition is linked to other oral traditions. The near tradition is that of experiments within twentieth century European theatre and dance: Stanislavsky, Meyerhold, Vakhtangov, Eisenstein, and Okhlopkov; Dalcroze, Appia and others who worked at Hellerau in the years just before World War One; Artaud. But the closest theatrical link is Juliusz Osterwa’s Reduta theatre in Poland between the World Wars. The far traditions are more complicated. They include ancient gnosis and hermetics7, as well as the closely related work of Gurdjieff. And Hasidism, especially Buber’s interpretation of it. There is also an American connection, itself a transformation of German‑ Jewish intellectual life and its coalescence with American utopian tendencies to form “new age” practices. Here gestalt therapist Fritz Perls comes to the fore. No one doing scholarship on Grotowski (in English) has gone deeply enough into these various theatrical, mystical, and intellectual sources, linking them to each other and to Grotowski. What I write concerning Grotowski’s sources, I offer as a step along the way.

Stanislavsky, Meyerhold, Osterwa

Grotowski takes from Stanislavsky the axiom that continuous actor training is fundamental, and that this training is before anything else “work on oneself.” Grotowski: “This expression‑‑ this formula, ‘work on oneself’‑‑is one that Stanislavsky always repeated and it is from him that I take it” (1996:89). What changes over the years is how Grotowski interprets not only the work but the self; how the “actor” as a someone who presents a character for an audience recedes, to be replaced by “performer,” or “doer,” a person using techniques drawn from theatre and elsewhere but for purposes that are trans‑theatrical. During the theatre of productions phase, Grotowski explored the tensions between the actor, the space, and the audience.

Spectators were deployed through environmental theatre spaces the better to witness the actors in their celebrations and agonies (in the ancient Greek sense). The scenography, far from fostering empathy or audience participation, radically separated spectators from performers. Witnesses peered over a fence at the immolated Constant Prince, sat at Dr. Faustus’ banquet table, watched the inmates construct their own crematorium in Akropolis. But these spectators were never brought into the work directly; and the physical proximity generated a metaphysical distance. Grotowski’s actors were so intense, so much into what they were doing, that even when a whisker away from you, they were in another world. Only with the starkly simple space of Apocalypsis cum Figuris, the Laboratory’s last work to which a general public was admitted, did spectators emerge as participants. During the New York performances attendees sat on the floor at the edges of a large room–the Washington Square Methodist Church cleared of all furniture. The actors performed in the center, at the same level as those watching. Lighting was one huge fresnel lying on the floor like a fallen sun. At a point in Apocalypsis’ life, Grotowski began to invite some spectators to stay after the show. When the rest of the public left, the Laboratory’s actors and the visitors began mutual performative explorations.

In this way, Grotowski segued from the Theatre of Productions to Paratheatre. In my view, this transformation was stimulated by Grotowski’s encounter with American youth culture, gestalt therapy, and new age religions. But I am getting ahead of the story.

The questions Grotowski confronted in every production before Apocalypsis concerned the following: for whom were the performances made, how could a textual‑gestural montage be constructed, and how could the spaces of performance contain and express the overall life of the event? In answering these questions, Grotowski followed and then superseded Stanislavsky. Stanislavsky always put the actor at the center. He accepted the proscenium stage space and playwrights’ texts as given. Grotowski, aware of what Meyerhold, Vakhtangov, and Okhlopkov attempted took from these experimenters without abandoning Stanislavsky’s core quest: the work of the actor on himself. Stanislavsky’s “method of physical actions,” developed in the 1930s, was probably influenced by Meyerhold’s bio‑mechanical work of the 1920s. Meyerhold emphasized dancelike acrobatic movements performed with the efficiency of (the then admired) assembly line. Grotowski’s adaptation of Stanislavsky and Meyerhold, reshaped by other influences still to be discussed, were the “association exercises” and “plastiques” (movement work). These were freer than Meyerhold’s bio‑mechanics, more set than Stanislavsky’s or Vakhtangov’s acting etudes. The exercises consisted of specific movements‑‑rotations, lifts, and stretches of limbs, torso, head, face, and eyes‑‑which took on intensity, rhythm, and emotional coloring from whatever “associations”‑‑feelings, memories, near‑dreams‑‑a person might have while executing the movements8.

But even while still making productions for a public, however tiny, Grotowski was aiming at targets other than theatre. Towards a Poor Theatre is full of allusions to the spiritual path. Theatre was his means not an end. The goal was not political, as with Brecht; nor artistic, as with Stanislavsky; nor revolutionary, as with Artaud. Grotowski’s goal was spiritual: the search for and education of each performer’s soul. The contradiction, power, and beauty of the Laboratory Theatre’s work in the 1950s and ’60s came from Polish circumstances. Grotowski and his group had to make theatre, that’s what the government subsidized them to do. So that is what he and his colleagues in Opole and later Wroclaw did. But, as already noted, Grotowski chose theatre over medicine and Hindu studies because the rehearsal process offered him a chance to work in relative freedom, behind closed doors. This suited him just fine: his interests ran to the esoteric and hermetic anyway. Grotowski told me in Copenhagen:

Because theatre was at that time the only possibility where I would not be censored. Censors could squelch playtexts, they could censor the final dress rehearsal. But most of the real work in theatre takes place during rehearsals; and gestures and music and such did not have “meaning” the censors could grasp, could censor. The censors didn’t enter the rehearsals. They only came in when a performance was ready for the public. So theatre was a place where one could work more or less freely, for a long time in preparation.

A very shrewd appraisal. A strong argument for emphasizing process over product. But there is more to it, of course. With Grotowski there are always layers of significance, double or quadruple meanings, contradictions.

In making a “theatre laboratory,” Grotowski consciously emulated Neils Bohr, the nuclear physicist his brother once worked with. But the experiments of this theatre laboratory had more in common with Grotowski’s closest Polish predecessor, Osterwa. Osterwa believed that acting was a “calling,” that actors play vis‑a‑vis spectators but never for spectators.

Kazimierz Braun traces the importance of Osterwa’s Reduta to Grotowski:

Who was Osterwa? An actor, a director, a teacher, a reformer. […] Reduta […] was a theatre, but at the same time it was an acting workshop and a school. All events of life and artistic activity were communal, with a common kitchen and money. Specialists of varying skills were called to rehearsals as advisors and teachers. Actors and spectators met after performances to discuss the work. All this was based on Osterwa’s belief that the theatre is a process, an inter‑human process artistically conditioned.

Osterwa’s approach to the theatre was based on the contention that its mission is above all spiritual, educational, and moral. Work in the theatre should be based on the individual ethics of actors and directors, of all the people involved in creating theatre, including the spectators. […]

Osterwa experimented with special methods of rehearsal. He was among the first in Europe to introduce actor training separate from rehearsals. He also experimented with audience participation. He used to bring actors and spectators into close contact, even merging them […]. Osterwa’s most acclaimed production was The Constant Prince […]. Osterwa himself playing the title role made this play a ritual of sacrifice, obviously (as Grotowski did later on) comparing the Constant Prince to Jesus Christ. Osterwa’s production of The Constant Prince was in the open air, lit‑‑partially‑‑by open fire. […]

Grotowski took much from Osterwa: the idea of the actor sacrificing her/himself for the spectators, his pattern of comparing the studio/theatre to a monastery, his attempts to include spectators into the theatrical action. Even on the simply external level, however significant, Grotowski took an old Reduta trade mark [a graphic emblem] for “Laboratory Theatre” (1986:235‑36).

Grotowski followed and absorbed Osterwa; was like his predecessor and went beyond him; made a new theatre under Reduta’s old sign.

Dalcroze and Gurdjieff

More intriguing, because less well known, are the parallels between Grotowski’s researches and Emile Jaques‑Dalcroze, Martin Buber, and Gurdjieff. These and many others including Shaw, Appia, Stanislavsky, and Nijinsky participated in or saw work at Hellerau, near Dresden. The Hellerau project lasted only from 1911 to 1914, before being snuffed out by World War One. Hellerau looked back to Wagner’s gesamtkunstwerk and forward to the Bauhaus and Black Mountain College. At Hellerau, the idea of art, health, and education converged. Dalcroze’s eurhythmics were reshaped under Adolph Appia’s influence into an integrated dance‑music‑theatre art. Buber participated in theatre at Hellerau9; and the physical plant was entrancing enough to induce Gurdjieff to seek it in 1922 for his headquarters. But the link joining Dalcroze, Gurdjieff, and Grotowski is more than real estate.

At Hellerau–a “radiant meadow”–what was Dalcroze’s work? Hellerau was more than a theatre, it was a model community for living in harmony with nature and art. In the theatre building, the whole space was designed. Spectators and performers illuminated by diffused lighting watched and enacted movements expressing not narration but feelings. Dalcroze worked not with individuals, but with groups, crowds. The goal was an integration of music, dance, theatre, lighting, and scenography. Dalcroze said that “only an intimate understanding of the synergies and conflicting forces of our bodies can provide the clue to this future art of expressing emotion through a crowd; while music will achieve the miracle of guiding the latters’ movements‑‑grouping, separating, rousing, depressing, in short, ‘orchestrating’ it, according to the dictates of natural eurhythmics” (1976 [1921]:x). Dalcroze did not investigate Buber’s “ich und du,” the intimate dyad so important to Grotowski. Nor did Dalcroze go as far as Gurdjieff and Grotowski: asserting that “objective” movement and song is truth embodied, felt, and performed. But Dalcroze’s work is an important step along the way.

To Gurdjieff dance‑‑sacred movement‑‑was the core of the received wisdom of the oral tradition. Gurdjieff described himself as a “dancing master,” aligning himself with Sufi masters whose whirling dances embodied their understanding of the world10. Throughout most of his life as a teacher, Gurdjieff staged dances, sometimes for large paying publics, as in Paris in 1923 and New York in 1924, sometimes privately for patrons or disciples. Movement, Gurdjieff taught, brings people close to the truth of things. According to James Moore:

The interface between Dalcroze eurhythmics and Gurdjieff’s Sacred Dance dates from the Tblisi period when Jeanne [de] Salzmann put her Dalcroze pupils at Gurdjieff’s disposition for the demonstration at the Opera House on 22 June 1919. In winter 1921, when Gurdjieff came to Hellerau more or less under the patronage of Dalcroze, he evidently presented a programme of sorts. […]. Jessmin Howarth and Rose Mary Nott‑‑Dalcroze students who abandoned eurhythmics and attached themselves to Gurdjieff around this time‑‑later became respected teachers of Gurdjieff’s dances. When Gurdjieff first arrived in Paris in July 1922, he established himself in the Institut Jacques‑Dalcroze in the Rue de Vaugirard. (1991:362)

Moore says the “question of direct personal contact between Gurdjieff and Dalcroze is clouded.” But whether or not the two men ever personally interacted, they were linked by Jeanne de Salzmann who, more than putting her dancers at Gurdjieff’s “disposal,” became Gurdjieff’s closest disciple, the heir to his knowledge, the receiver of the oral tradition. In the body of de Salzmann, Dalcroze and Gurdjieff met. But what about Grotowski?

When Grotowski first met Peter Brook, a Gurdjievian of the highest rank, the Englishman thought the Pole

was the emissary of a lost branch of Gurdjieff’s school which survived in Poland after the emigration of Gurdjieff and his primary teachers to the West during the Russian revolution. Grotowski speculates that Brook’s conclusion was based on certain pronounced similarities between Grotowski’s objectives and rhetoric and the specialized terminology of Gurdjievian teaching, as well as Gurdjieff’s focus on embodied practice as a means for self‑remembering. […] What might have come as a surprise to Brook, however, was that Grotowski […] had never so much as heard the name of the Armenian master before that day (Wolford 1994:225)

Grotowski repeats the denial in a 1991 interview (Grotowski 1996). Is trickster Grotowski to be believed? Grotowski’s journeys as a young man took him to many of the regions Gurdjieff explored at the turn of the century: interior central Asia, China, India, Tibet–threading the ancient silk‑route into areas where Sufis danced, where Buddhism, Lamaism, Hinduism, and Islam feed each other. Even at the start of the Theatre of 13 Rows, Grotowski, like Gurdjieff, worked from a close inner circle, transmitting knowledge directly by means of dance, song, utterance, and intimate encounter. Granted that Grotowski was barely 30 when he met Brook, could it be that in his pursuit of esoteric knowledge – his research into old forms of Christianity, his studies of the Tao, Vedism, yoga, Sufism, gnosis, and shamanism – Grotowski never heard the name “Gurdjieff”?

Or maybe it is that once Grotowski learned of Gurdjieff, and saw how close the intention of their work was, he drew certain elements from him. In discussing Objective Drama in the 1980s, Grotowski uses terms very much like those Gurdjieff employed discussing the objective laws of art. “In real art,” Gurdjieff said, “there is nothing accidental. It is mathematics.

Everything in it can be calculated, everything can be known beforehand. […] It will always, and with mathematical certainty, produce one and the same impression. […] This is real, objective art” (Ouspensky 1949:26‑27). Ouspensky asked Gurdjieff if this art exists now? “Of course. The great Sphinx in Egypt is such a work of art.” But in our own day? Gurdjieff told of what he saw “in the desert at the foot of the Hindu Kush,” an ancient god or devil. “[T]his figure contained many things, a big, complete and complex system of cosmology. And slowly, step by step, we began to decipher this system. […] In the whole statue there was nothing accidental, nothing without meaning” (27). Gurdjieff’s desire to produce his own “objective art” led him to synthesize what he called The Movements from different sources. According to Ouspensky, “We began rhythmic exercises to music, dervish dances, different kinds of mental exercises, the study of different ways of breathing, and so on” (372). Over time Gurdjieff put these together into a “ballet” or “revue” which as performed in Tiflis, Paris, and New York “there entered […] dances, exercises, and the ceremonies of various dervishes [mostly Mevlevi] as well as many little known Eastern dances” (382). Michel de Salzmann, Jeanne’s son and a leading Gurdjievian, writes that Gurdjieff’s “aim was to show the forgotten principles of an objective ‘science of movements’ and to demonstrate its specific role in the work of spiritual development” (1987:139). The Movements also show Dalcroze entering the work via Jeanne de Salzmann. Moreover The Movements are similar to Grotowski’s Motions, a basic exercise developed during the Objective Drama phase. In Motions, as in Movements, the physical details are very precisely codified, repeated in exactly the same way.

Having neither done nor witnessed The Movements or Motions, I won’t presume to compare the two. However, photographs and descriptions indicate what I feel is more than a coincidence. The similarities can be explained two ways. Either Grotowski took something from Gurdjieff or both Gs drew from the same sources. Whichever, what interests me is the underlying drive of the work.

Speeth says The Movements “are a kind of meditation in action that also has the properties of an art form and a language” (1989:83, 88). This could just as well be said of Downstairs Action and Action. Grotowski, in an interview published in Encounters with Gurdjieff, observes:

The Movements: they are something fundamental. Gurdjieff is rooted in a very ancient tradition, and at the same time he is contemporary. He knew, with a true competence, how to act in agreement with the modern world. It is a very rare case. […F]rom the moment I began to read about Gurdjieff’s work, the practical comparisons not only had to corroborate but also to touch me, it is obvious. It would be difficult to analyze: which details, which elements? Because there is also a danger of asking oneself: “From where comes this element, and from where another?” What is important is not that they come from somewhere, but that they work. This criterion, is it clear? This means: There is an element which works, and it is corroborated here and there. In the case of Gurdjieff, the impact is of something both very ancient and contemporary. Both the tradition and the research are strong. And at the same time there is there a manner of posing some ultimate questions. Here we are no longer in the technical data, but in the depths of ideas, with all the dangers that this brings (1996:93‑94).

Isn’t Grotowski describing himself as much as Gurdjieff? The convergences are just as clear when he talks about his 1990s work at Pontedera:

At present my work is very much linked to ancient song, to “vibratory” song. In a period of my “Laboratory Theater,” for example in The Constant Prince, the research was focused less on song, though in a certain way it was already a sung action. I have always considered it very strange to want to work on voice or song, or even pronounced words, while cutting them off from corporeal reactions. The two aspects are very much linked; they pass through each other. […] At my Workcenter in Pontedera, in Italy, as far as technical elements are concerned, everything is as it is in the performing arts; we work on song, on the vibratory qualities of song, on impulses and physical actions, on forms of movement; and even narrative motifs may appear. All this is filtered and structured up to the point of creating an accomplished structure, an Action, as precise and repeatable as a stage production. Nevertheless it is not a production. One can call it art as a vehicle or even the objectivity of the ritual. […] When I refer to ritual, I speak of its objectivity: that is to say that the elements of the Action are, through their direct impact, the instruments of the work on the body, the heart, and head of the “doers” (Grotowski 1996:87‑88).

Ironically, Grotowski the stage director goes out of his way to deny the theatre while Gurdjieff the spiritual master behaved so often as an impresario.

What tethers the Gs to each other, finally, is their search for gnosis, an ancient religious practice of the interior Middle East, Central Asia, Iran, Afghanistan.

Sufi e Hasidi

Gnosis is a Greek word meaning, roughly, “knowing.” It is cognate with the English “know” as well as with Sanskrit jnana, the yoga of wisdom or knowing. Gnosis is an “underground,” sometimes heretical, tradition in Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. Gnosis is affined with Sufism and the hermetic religion of Egypt and Greece. The precise sources of gnosis are disputed. Some say Egyptian, some Hebrew, some Iranian. Probably all these, mixing effervescently during the two millennia before Christ. Gnosis has long been resistant to orthodoxy, whether Jewish, Christian, or Islamic. In some manifestations‑‑the teachings of Mani (216‑77), for example‑‑gnosis was condemned as heresy. The Egyptian‑Greco root of gnosis is Hermes Trismegistos, “thrice great Hermes,” who proclaimed, “He who knows himself, knows all.” Such knowledge can be tragic, ask Sophocles’ Oedipus. This “self” is not personality, but the identicality of brahman and atman: that which in each is All. This impersonal self Oedipus sees after he stabs out his eyes. Such blindsight Krishna gives to Arjuna in the Bhagavad‑Gita.

KRISHNA:

But you cannot see me

with your own eye;

I will give you the eye to see

the majesty of my yoga

SANJAYA:

O King, saying this, Krishna

the great lord of yoga,

revealed to Arjuna

the true majesty of his self […]

The brightness of a thousand suns

burning together in the sky

is the light of that great self.

And Arjuna saw the whole universe

converged into one body […]

ARJUNA

O, God! […]

You are the imperishable.

Beginning, middle, and end

you do not know.

Your arms, numberless.

Your eyes the sun and moon,

your mouth flaming fire

burning up all that is.11.

Arjuna has the courage to ask: “Who are you in this terrifying being I see?” “I am time, that which swallows all,” says Krishna. Gnosis knows that atman‑brahman is an absolute that can be experienced but not reduced to discourse. Gnosis is expressed in metaphors and practices. Gnosis is an upward journey along the path of the chakras, the ancient yogic wheels of energy within each human, from the lowest center at the base of the spine upwards to the high center in the skull. Gnosis is the scattered sparks of original fire, embers that can be gathered into larger and brighter centers of light. It was in search of these miraculous embers, these “sources,” that Gurdjieff and Grotowski undertook their journeys geographical, mystical, and theatrical.

In the 1991 interview previously cited, Grotowski talks about how his work

is like a kind of elevator, but an elevator as in very ancient times, in the so‑called primitive societies: a big basket with a rope by means of which the person who is inside, by his own effort, has to move himself from one level to another. The question of verticality means to pass from a so‑called coarse level‑‑in a certain sense one could say an “everyday” level‑‑to a level of energy much more subtle or even toward the higher connection [Grotowski’s italics]. At this point to say more about it wouldn’t be right (88‑89).

But he does say more about it. Grotowski describes how in Action, songs are the way of rising toward the subtle and of making the subtle descend “to the level of the more ordinary.” These songs are “very ancient […] linked to the ritual approach, because that is the material of our work” (90‑91).

Grotowski knows that different cultures, at different periods, have different terms for the same system. He finds analogous theories and practices of the upward and downward flow of energy in Gurdjieff, in the theory of chakras, in India, China, and Europe. Still he resists “naming,” reducing to discourse.

In general, one can say that we try not to freeze language. an “intentional” language is used, i.e., one which functions only between the people who are working. There, where one approaches the more complex issues, the so‑called inner work, I avoid as much as possible any verbalization (92).

Then, exasperated by the interviewer’s insistence, “But if you are pushing me toward the language of religions then … O.K. … I let myself go” (105). In a burst of references, Grotowski ranges over fables expressions figures metaphors: Jacob’s ladder, Kali, the Shekhinah, jnana, gnosis. “In the traditions, there exist several versions about the two currents of the world: the descending and the ascending. This can take quasi‑gnostic forms of explanation […], but it also exists in the sciences. The appearance of life and consciousness would be like a small countercurrent because, in the scientific sense the world has been created through entropy and in entropy. A kind of an opposite process is the appearance of life […]” (105‑6).

There the interview abruptly ends.

When Mevlevi Sufi dervishes dance, the right palm faces upwards receiving divine solar energy, the left down transmitting the energy into the earth, the people. As in gnosis, the work is to gather energy, focus it, and redirect it. Work similar to that of hasids seeking the Shekhinah or yogins training their serpent kundalini up the ladder of chakras. Each are part of the “small countercurrent” acting against universal entropy. Sufis can be of any religion, or (as Grotowski) none. They are “hidden more deeply than the practitioner of any secret school. Yet individual Sufis are known in their thousands […] in the lands of the Arabs, the Turks, the Persians, Afghans, Indians, Malays” (Shah 1971:18). Sufi knowledge is various and complex12, reaching back and into Toth/Hermes13, gnosis, Hebrew, Egyptian, Greek, and Islamic sources. Sufism is an embodied practice, existing in its dances and songs. The ceremonies of the Mevlevi Order founded in the 13th century in Konya (today’s Turkey) by Mevlana Celaleddin Rumi, poet and mystic, was closely studied by Gurdjieff.

In 1920 Gurdjieff led his Institute into exile in Turkey, and studied the techniques of the Rufai and Mevlevi rituals […]. Later his troupe travelled across Europe and the U.S.A., always incorporating some elements of the Whirling Dervish movements combined with other dervish dancing from Central Asia, Christian Assyrian ritual, and folk and country dances from Turkey and Transcaspia. The male members of his company were generally attired exactly like the Whirling Dervishes (Halman and And 1983:73‑74).

Dervishes, The Movements, Motions, Downstairs Action, Action are linked by the kind of movement used, the sources of that movement, and by purpose and function. Not to reduce Grotowski to Sufism, but to indicate Sufism as another strong presence within the Grotowski‑body (not his own so much as those he has trained most intently: Cynkutis, Cieslak, Richards).

If Sufism (and all it refers to and synthesizes) is a key ingredient in Grotowski’s work, his way of working is Hasidic. To find Sufis, yogins, and other Asian knowers, Grotowski had to travel. Hasids were all around him in Poland, even as they went up in the smoke of the Holocaust (a vanishing represented in Akropolis). Modern Hasidism arose in Eastern Europe in the mid‑18th century among followers of Yisrael ben Eliezer, the Baal Shem Tov (“Master of the Good Name”) known by his acronym, Besht. Before Besht was Shabbetai Tsevi who, in 1665, during a period of Jewish suffering unequalled in Europe before the Holocaust, proclaimed himself Messiah and “was venerated as ‘our lord and king’ from Cairo to Hamburg, from Salonika to Amsterdam from Morocco to Yemen, from Poland to Persia” (Werblowsky 1987:193). Then when in 1666, imprisoned by the Ottomans and told to convert or die by torture, Shabbetai traded yamulka for turban, a great disillusionment gripped Jewish communities, preparing the way for Besht and Hasidism. Hasids rejected Shabbetai. Instead they emphasized practices connected to the Kaballah and the Zohar. As in gnosis, but in terms that affirm Jewish monism (as opposed to gnostic dualism), Hasids believe that God “contracted” himself “away from the world which vacated the space in which the cosmos was going to be created from the divine light of the godhead, the first exile of God” (Dan 1987:207). Or as Martin Buber puts it:

The Kabbalistic teaching, which Hasidism built into its own system, […] teaches that the firestream of creative grace poured itself out over “the vessels,” the first created primal forms, in all its fullness; but the vessels could not stand it, they “broke into pieces”‑‑and the stream flashed forth into the infinity of “sparks,” the “shells” grew round them, want, defilement, evil came into the world. But He does not leave it to lie alone in the abyss of its struggles; his Glory itself descends to the world, following the sparks of his creative passion; His Shekhinah goes into it, goes into “Exile,” lives in it; she lives with the sorrowful, suffering, created things in the midst of their defilements‑‑eager to redeem them (1948:105‑06).

[…]

God’s Shekhinah descended from sphere to sphere, wandered from world to world, enveloped itself with shell upon shell, until it was in its furthest exile‑‑in us. In our world God’s fate is being accomplished (1948:64‑67).

Hasids seek the Shekhinah, whom the Greeks called Sophia, the light of wisdom, in order to break through the “shells” and gather her “sparks.” In Grotowski’s terms, this search for the Shekhinah is his “Theatre of Sources,” his “Objective Drama,” his “Art as Vehicle.”

Grotowski says that Buber‑‑”the last great Hasid”‑‑affected him more than Gurdjieff. “I knew about the Zohar from the time I was 10 years old,” Grotowski told me, “and Buber from about age 18.” But what kind of impact did Buber‑Hasidism have? Certainly Grotowski’s method of working with those he once called actors and now calls “performer” or “doer” has the quality of “ich und du,” an intimate dialogue, unique and unrepeatable. But there is more. Hasids worship God directly, stressing the “mystical contact with God through devequt, usually attained while praying but also achieved when a person is working for his livelihood or engaged in any other physical activity” (Dan 1987:207). Hasids believe in the “zaddik,” the righteous person, of whom there are precious few.

[…] in every generation there are some righteous persons who can and should, by their outstanding mystical worship, correct the sins and transgressions of lesser‑endowed people. […] This theory demands that the tsaddiq be in constant movement between good and evil, heaven and earth.

[…] He has to be close to the evil that he is to correct, subjecting himself to the process of a “fall” […] (Dan 1987:208).

Grotowski’s “primal elevator,” the rising up, the falling down; the persistent theme of seeking‑and‑sacrificing in The Constant Prince, Akropolis, Apocalypsis cum Figuris, reconfigured but not abandoned in the various phases of “cultural research” from the paratheatrical experiments to Art as Vehicle, shows strong Hasidic affinities.

But it is not in the philosophical systems that Hasidism and Grotowski most closely approach each other. It is in Grotowski’s style of leadership, his relationship to his inner circle and they to the wider world. Rebbe Grotowski is the center from whom all radiates. His authority is unquestioned, yet gossiped about. Stories about him abound. His aura surrounds, protects, and illuminates him. The core of what he has to teach cannot be put into words. He is always seeking.

The Baalshem himself belongs to those central figures in the history of religion who have done their work by living in a certain way, that is to say, not starting out from a teaching but aiming towards a teaching, who have lived in such a way that their life acted as a teaching, as a teaching not yet translated into words (Buber 1948:2).

To see those who serve Grotowski accomplish their work, is to witness a Hasidic community and its rebbe. Grotowski answers his disciples’ love not sanctimoniously or sentimentally, but in typical Hasidic fashion: paradoxically, with wit, demanding unremitting hard work, radiating light and energy. This is, as Buber points out, like Zen. “In both [Zen and Hasidism], man reveres human truth, not in the form of a possession, but in the form of a movement, not as a fire that burns upon the hearth, but, speaking the language of our time, like the electric spark, which is kindled by contact” (1948:194).